C# 7 Features Worth Knowing - Part 2

In this post we’ll see some more new features from C# 7.0.

In the first part of this series, we talked about some new features from C#, namely: literal improvements, out variables, more expression-bodied members and throw expressions.

Today we’ll see: Tuples and Local Functions. But before we go on, I’d like to thank my friend Gunter Italiano Ribeiro for reviewing this article.

Tuples

Have you ever felt the need to write a method that returned more than one value? I’d bet you have. In previous versions of the C# language, there were some options available. You could use an out parameter, or even create a type for that, but each one of these had their own problems. Out parameters are non-intuitive and can complicate the design; creating a custom type just for this can be overkill.

In C# 7.0 you have a new option, by using tuple types and tuple literals. With this feature you can easily declare a method that returns more than one value. Let’s see an example:

You’re probably familiar with the TryXXX pattern, used, for instance, in the System.Int32 BCL type. These sort of methods generally use an out parameter to return the resulting value (or the type default value, in case the parsing operation does not succeed).

The method above contains a TryParse method in the ZipCode class. Take a look at the method’s signature.

When you write more than one type in the method’s return, you’re using a tuple type. Don’t worry, you’re going to get used to it.

Right at the start of the method, we pass the specified text for a private method that actually performs the validation and returns a boolean value.

After the validation, we return a tuple literal, which consists in a new instance of the ZipCode class and a boolean flag indicating whether the parsing operation succeeded.

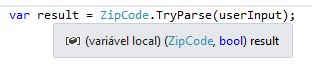

Nice, but what about the other side? How the function caller deals with this sort of return value? Let’s see:

If you hover over the variable name, you’ll see its type described, unsurprisingly, as (ZipCode, bool).

You can access each tuple element by using zipParsingResult.Item1, zipParsingResult.Item2, and son on.

However, you’re not forced to use the default names. There’s nothing stopping you from using more descritive naems:

The calling code becomes more readable:

There’s still another way of accessing a tuple’s items. By using a functionality called Deconstruction, you can easily split a tuple’s elements into variables.

You can declare the variables by using their types:

Type inference also works here, and you have two options: you can use the var keyword for each variable, or to use it just once for all variables, placing it outside the parenthesis.

You don’t even need to declare the variables at the deconstruction moment. It’s perfectly valid to deconstruct a tuple into already existent variables.

Some notes

Tuples are Value Types. Equality for tuples works in the way you’d probably expect: two tuples are considered equals if their items have the same values and they return the same HashCode. The names of the items are not relevant

Assignment also works in the intuitive way. As long as they’re assignable to each other, two tuples can freely be assigned to one another. As in the previous case, the item’s names don’t matter.

Currently, for this feature to work, you must install a nuget package called System.ValueTuple. In Visual Studio, go to Tools > NuGet Package Manager > Package Manager Console..

The Package Manager Console Windows will be shown. Type Install-Package System.ValueTuple and press ENTER.

But what about System.Tuple?

Maybe you’re wondering: why so much noise about tuples, if the .Net Framework has had the System.Tuple reference type since its 4.0 version? Why don’t we just stick to the older type?

Well, this Stack Overflow answers it pretty well, but I’ll try to summarize it here.

Firstly, as already mentioned, the older type is a reference type, and the new one is a value type, with all the usual implications.

But the really important differences have to do with convenience and readability. If you use System.Tuple there is no deconstruction; you can only access the items by using the default names, which makes the code harder to read and understand.

Local Functions

A Local Function is exactly what its name suggests: a function that can be declared inside another function.

As you’ve noticed, the inner function can access the values available for the outer function.

Of course, the example shown above is deliberately simple; in production, you’d probably just write the code in Log() in the external methods and be done with it.

It’d also be possible to use a delegate for that:

It seems that everything we can do with a local function is also possible to do with private methods or delegates. Do we really need this feature?

Giovani Bassi give us some reasons to use this feature:

- Sintaxe consistente com a já utilizada em métodos;

- Não há necessidade de criar um delegate, ou referenciar Func, Action, ou algo parecido;

- Lambdas e delegates causam alocações extras, funções locais não;

- Ref e out são permitidos;

- Tipos genéricos são permitidos;

- É possível referenciar funções ainda não declaradas.

In free translation:

- Sintaxe consistent with the one already used in methods;

- No need to create a delegate, or reference Func, Action, or something like that;

- Lambdas and delegates cause extra allocations, local functions don’t;

- Ref and out are allowed;

- Generic types are allowed;

- It’s possible to reference functions not yet declared.

Of course you could just use a private method. But the local function has this nice property of not being acessible to the rest of your class, making it impossible to be accidentally called.

Mads Torgersen shows us a situation for which local functions are the perfect solution:

As an example, methods implemented as iterators commonly need a non-iterator wrapper method for eagerly checking the arguments at the time of the call. (The iterator itself doesn’t start running until MoveNext is called). Local functions are perfect for this scenario:

You could turn Iterator() into a private method, sure, but that would be: 1) redundant and not very elegant, since it would require you to repeat the same signature from the outer function; and 2) less safe, because another part of the code could call the method without performing the validation.

Conclusion

Today we’ve talked about Tuples and Local Functions, two new features from C# that, at first sight, can look harmless, but have potential to change the way you write code in interesting ways.

Local functions? At first, I didn’t really liked it, I must admit. Or rather: I couldn’t understand what would they be useful for. After some research, I understood their use cases.

With tuples, it’s a whole other story. I believe every C# developer with some experience under their belt has felt the need to return more than one value from a method and was frustrated with the available options. Now using tuples we finally have an elegant, easy-to-use solution, that makes the code less clumsy and more readable.

Not everything is perfect though. Some developers already express concerns with these features. For instance, local functions could encourage the creation of large methods.

Tuples, on the other hand, could be over-used in situations that require objects, making the code more procedural.

My opinion about all of this is very simple: every tool can be abused. It’s up to us, professionals, and to our teams, to exercise our common-sense while using these (and other) features. By the way, as I mentioned in my article about private methods, code review and/or pair-programming can be of invaluable help in situations like these.

Thanks for reading. See you next time.

References

- https://blogs.msdn.microsoft.com/dotnet/2017/03/09/new-features-in-c-7-0/

- https://www.lambda3.com.br/2016/04/novidades-do-c-7-local-functions/ (pt-br)