Git Create Branch: 4 Ways To Do It

Editorial note: I originally wrote this post for the Cloudbees blog. You can check out the original here, at their site.

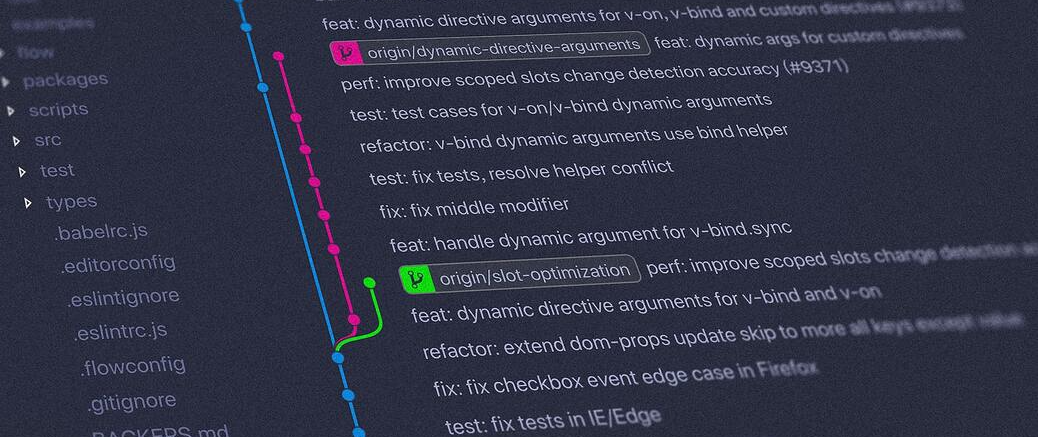

If you write software for a living, then I can say with confidence you’re familiar with Git. The tool created by Linus Torvalds has become synonymous with version control. And without a doubt, one of Git’s best features is how it takes away the pain of branching and merging. There are several ways you can create a branch in Git. In this post, we’ll review some of them. Then we’ll end with a little reflection on Git’s branching model and branching in general.

Creating a Branch From main

You create branches in Git, unsurprisingly, by using the branch command. Like many other Git commands, branch is very powerful and flexible. Besides creating branches, it can also be used to list and delete them, and you can further customize the command by employing a broad list of parameters. We’ll begin with the first way of creating a branch. Let’s say you want to create a new folder called “my-app”, enter it, and start a new Git repository. That’s exactly how you’d do it:

mkdir my-app

cd my-app

git init

Now you have a new, empty Git repository. But empty repositories are boring. So what about creating a new markdown file with “Hello World!” written in it?

echo Hello World! > file.md

If you run “git status”, you should see a message saying your file is untracked:

$ git status

On branch main

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

file.md

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

Untracked files are also uncool, though, so let’s track it:

git add file.md

And finally, let’s create our first commit:

git commit -m "First commit"

We now have a repository with one branch, which has exactly one commit. That might not sound like the most exciting thing in the world (because it really isn’t), but it’s certainly less boring than having a repo with no commits at all, right?

Now, let’s say that for whatever reason you need to change the file’s content. But you don’t feel like doing that. What if something goes wrong and you somehow spoil the beautiful, pristine content of your file? (Yeah, I know it’s just some stupid file with “Hello World!” in it, but use the wonderful powers of your imagination and think of the file as a proxy for a much more complex project.) The solution to this dilemma is, of course, creating a new branch:

git branch exp

So now we have a new branch called “exp”, for experimentation. Some people who are used to using different versioning systems, especially centralized ones, could say the branches have the same “content.” This isn’t entirely accurate when talking about Git, though. Think of branches like references that point to a given commit.

Creating a Branch From a Commit

Suppose that, for whatever reason, we give up on our experiment, without adding a single commit to the new branch. Let’s go back to main and delete the exp branch:

git checkout main

git branch -d exp

Now that we’re back to a single branch, let’s add some commits to it, to simulate work being done:

echo a new line >> file.md

git commit -a -m "Add a new line"

echo yet another line >> file.md

git commit -a -m "Add yet another line"

echo one more line >> file.md

git commit -a -m "Add one more line"

echo this is the last line i promise >> file.md

git commit -a -m "Add one last line"

Imagine that after doing all this “work,” you learn that, for whatever reason, you need to go back in time to when there were just two lines in the file and create new changes from then on. But at the same time, you must preserve the progress you already made. In other words, you want to create a branch from a past commit. How would you do that? In Git, each commit has a unique identifier. So you can easily see this using the git log command. To create a new branch based on a specific commit, just pass its hash as a parameter to the branch command:

git branch new-branch 7e4decb

As an aside, you don’t even need the whole hash most of the time. Just the first five or six characters will do it.

Creating a Branch From a Tag

If you’re a little bit more experienced with Git, then you should be familiar with the concept of tags. You use tags to indicate that a given commit is important or special in some way. For instance, tags are generally used to indicate the actual versions of a product. If you’ve been working in your application for a while and you believe it’s time to release version 1.0, what you’d typically do is bump the version numbers wherever necessary, committing those changes and then adding a tag to that specific point in time. To create a tag, you’d usually run something like this:

git tag -a v1.0 -m "First major version"

The “-a” parameter indicates this is going to be an annotated tag. In contrast to a lightweight tag, this is a full-blown Git object, containing pieces of information such as the committer’s name and email, the timestamp, and a message. Now you have a tag, an indication that this particular point in history is special and has a name.

Nice. You can continue doing work, as usual, creating and committing changes that will be part of the 1.1 version. Until a bug report comes in. Some clients that were updated to the 1.0 version of the product say an import feature isn’t working as intended.

Well, you could theoretically fix the bug in the main branch and deploy it. But then the clients would receive features that are potentially untested and incomplete. That’s a no-no. So what do you do? The answer: You create a new branch from the tag you’ve created to indicate the major version. You fix the issue there, build, and deploy. And you should probably merge this back to main afterward, so the next releases contain the fix. How would you go about that? Easy:

git branch <NAME-OF-THE-BRANCH> <TAG>

More specifically, using our previous example:

git branch fix-bug-123 v1.0

After that, you can check out your new branch as usual. Or better yet, you could do it all in one step:

git checkout -b fix-bug-1234 v1.0

Creating a Branch in Detached Head State

Have you ever wished to go back in time? With Git this is possible…at least in regard to the files in our repository. You can, at any time, check out a commit if you know its hash:

git checkout <SHA1>

After running that, Git will show you a curious message:

You are in 'detached HEAD' state. You can look around, make experimental

changes and commit them, and you can discard any commits you make in this

state without impacting any branches by performing another checkout.

When you check out a commit, you enter a special state called, as you can see, “detached HEAD”. While you can commit changes in this state, those commits don’t belong to any branch and will become inaccessible as soon as you check out another branch. But what if you do want to keep those commits? The answer, unsurprisingly, is to use the checkout command again to create a new branch:

git checkout <sha1> #now you're in detached head state

# do some work and stage it

git commit -m "add some work while in detached head state"

git branch new-branch-to-keep-commits

git checkout new-branch-to-keep-commits

And of course, by now you know you can write the last two lines as a single command:

git checkout -b new-branch-to-keep-commits

Pretty easy, right?

Just Because You Can…Doesn’t Mean You Should

Git’s branching model is one of its selling points. It turns what in other source control systems is a painful and even slow process into a breeze. One could say that Git has successfully democratized branching for the masses. But there lies a serious danger. Due to the cheapness of branching in Git, some developers might fall into the trap of working with extremely long-lived branches or employing workflows or branching models that delay integration.

We, as an industry, have been there. We’ve done that. It doesn’t work. Instead, embrace workflows that employ extremely short-lived branches. You’ll have a secure sandbox in which to code without fear of breaking stuff or wasting your coworkers’ time. But does that have you asking, “How do I deploy code with partially completed features?” In that case, it’s feature flags to the rescue.

Git branches are a powerful tool. Use them wisely, and don’t abuse them. And when they’re not enough, employ continuous delivery/continuous integration along with feature flags—including specialized tools at your disposal—so your applications can get to the next level.

Found a typo or mistake in the post? Suggest edit ← The LINQ Join Operator: A Complete Tutorial C# Regex: How Regular Expressions Work in C#, With Examples →