Make Your Git History Look Beautiful Using Amend and Rebase

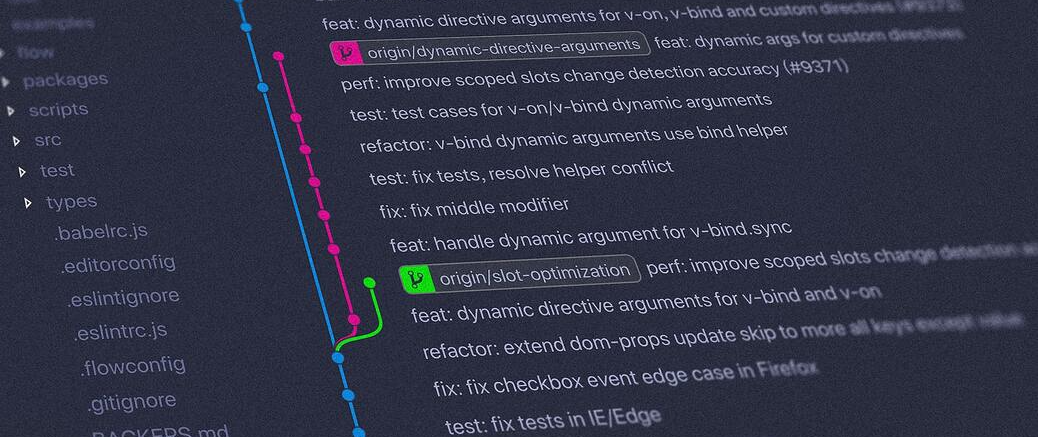

Photo by Yancy Min on Unsplash

You’re part of a small to medium-sized software team, and you’re envious of your co-worker’s Git history. They produce clean, well-structured histories with beautifully crafted commit messages. Yours, by comparison, looks like a train-wreck, full of descriptions such as “fix typo”, “add forgotten file”, and so on. You wonder how they do it.

The answer is simple: they cheat. You see, they probably make just as many mistakes as you do, but they use Git’s features to hide them. They then present a cleaner, nicer history to the world.

What they do is to rewrite history. Some version control tools treat history like it’s this super sacred thing. Git isn’t like that. It gives you power to rewrite history to your heart’s desire. So much power that you can even shoot yourself in the foot with it if you’re not careful.

In this post, I’ll show you how to use amend and interactive rebase to make your Git history look beautiful before publishing it. There won’t be much theory; I’ll walk you through some common scenarios, showing how I’d go about solving them.

Before wrapping up, I’ll teach you how to not shoot yourself in the foot with these commands. As I’ll explain, amending and rebasing are destructive actions, and there are situations in which you should not perform them.

Requirements

To follow along with this post, I assume you:

- Are comfortable working with the command line

- have Git installed on your machine

- know at least the basic Git commands

As I write this post, I’m on Windows, using Git version 2.38.1.windows.1 and typing my commands on Git Bash. If you’re on Linux or OSX, I guess everything will work just as fine, but I haven’t tested it myself.

Defining VS Code as Your Default Text Editor

Just a last digression before we really get started. Some of the commands you’ll be seeing throughout this post will require you to edit and save a text file. They do this by opening your default text editor as configured in your Git configuration file and waiting until you edit, save and close the file.

If you’re on Windows like me, using Git Bash, you’re default editor will be Vim. Vim is a command-line text editor, and some people find it intimidating. Though learning Vim requires some work, it’s not that hard to get the hang of it, and I’d recommend you invest some time to learn at least the most basic commands—specially how to quit!

However, Git allows you to pick other text editors as your default. If you have Visual Studio Code installed and want to use it, run the following command:

git config --global core.editor "code --wait"

Rewriting History: N Common Scenarios

I’ll walk you through a few common scenarios you might find yourself in which rewriting history will save you.

My Git Commit Message Has a Typo

You’re in a hjurry to fix this high priority bug. After hours of grueling debugging, you find the offending code, fix it and commit the change.

Only then you see you made a typo. How to fix that?

Let’s start by creating a repository for you to practice:

git init

Now, let’s add a new file and commit:

touch file.txt && git add file.txt && git commit -m "fix async request in getUsers() functino"

Run git log--oneline to see your commit message. You’ll see something like this:

Pay attention to the commit identifier, and maybe even write it down; it will be important later on. (Yours will be different than mine.)

Anyway, your message has a typo. How do you fix it?

Just run git commit --amend, exactly like that. Git will open your text editor and wait for you to edit the commit’s message:

fix async request in getUsers() functino

# Please enter the commit message for your changes. Lines starting

# with '#' will be ignored, and an empty message aborts the commit.

#

# Date: Tue Jan 10 19:14:17 2023 -0300

#

# On branch master

#

# Initial commit

#

# Changes to be committed:

# new file: file.txt

#

The first line is the actual commit message. The lines starting with the “#” are comments and will be ignored. Just fix the typo, save and close the text file, and you’ll have a brand new commit message. Run git log --oneline again to see it:

You’ll notice that the identifier (SHA-1) of the commit is now different than it was before—and also different than the one from the image above. I’ll get back to this later.

For now, you’ve successfully amended your commit message. Congrats!

I Forgot to Include a File

Sometimes you have several changed files and want to commit some but not all of them. In your hurry, you leave one or more files behind. How to fix this?

Amend to the rescue again.

To simulate this situation, let’s create a new file and also add a new line to the existing one:

touch file2.txt

echo 'New line' >> file.txt

A common mistake here is to run commit with the -a option, thinking it will include both files:

git commit -am "update file and add file2"

Run the command above. Then run git status. This is the result you’ll get:

On branch master

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

file2.txt

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

Fixing the situation is easy. First, you track or stage the forgotten file:

git add file2.txt

Then, use git commit –-amend again. Your editor will open, but in this case, there’s nothing wrong with the message. Just close the editor and you’re done: you now have an amended commit that includes the previously forgotten file.

But if you’re anything like me, you probably feel like a chump having opened your text editor for no reason at all.

Fortunately, you don’t always have to do that. When you just want to add one or more missing files without changing the commit message, you can use the --no-edit option, like this:

git commit –-amend –-no-edit

This way, Git won’t open your text editor, keeping the original commit message.

I Want to Merge Several Commits into One

Merging several commits into one is an operation called “squashing.” But why would you want to do that?

Well, it all boils down to your Git style. I like to make small commits, very often. Then, when I’m about to make them public (for instance, by opening a pull request) I squash them into a single commit, with a well-crafted message.

This is also a common requirement from open-source project maintainers, so it’s a good skill to have. Let’s learn how to do it.

First, let’s create three commits:

git commit --allow-empty -m "empty commit"

git commit --allow-empty -m "empty commit 2"

git commit --allow-empty -m "empty commit 3"

Creating text files for the sake of having commits gets old pretty quickly. That’s why I’m using the --allow-empty option, that enables me to create empty commits.

Now, let’s say I need to squash the three commits above into one. To do that, I’ll need to interactively rebase them. By doing an interactive rebase, you can perform tasks like:

- Reorder commits

- Drop one or more commits

- Change their messages

- Merge one or more commits together

Now comes the part that might be confusing, so please pay attention. Since we’re going to work with the three latest commits, we say we’re rebasing them on top of the fourth (from the top) commit.

So, use the command git log --oneline -4 to display the last four commits and then copy the SHA1 from the fourth commit from the result:

Copy the identifier from that commit and pass it to the rebase command, like this:

git rebase -i 45f90ca

Of course, your actual SHA1 value will be different. But there’s an easier way:

git rebase -i HEAD~3

To put it simply, HEAD here means the latest commit, and “~3” means “three commits before this one.”

After executing either of the two commands above, your editor will open, showing a text file that contains the messages from the three commits we want to rearrange, each preceded by the word “pick”. And after that, a set of instructions:

Notice that the commits here aren’t in the order you’re used to seeing them on Git. Instead of being in inverse chronological order, they’re in direct chronological order, and there’s a reason for that.

Each line you see above is a command that Git will execute when you confirm the rebase operation. There are several commands available, and pick is the default one. It simply means the commit will be kept as is. You can use drop to remove a commit, reword to edit a commit’s message, and so on.

The command we’re going to use is squash. Just replace the word pick with squash in the second and third commits, like this:

pick dd25df9 empty commit # empty

squash c68804f empty commit 2 # empty

squash a76fd60 empty commit 3 # empty

The squash command merges a commit with the one before. So, the third will be merged into the second, which will be merged into the first one. And that’s why the first one needs to be picked.

After editing the text like I told you, save and close the file. When you do that, your editor will be opened once again. This time, you’ll be prompted to write a commit message for the new commit that will emerge:

Replace the file’s content with “this is now a single commit.” Save and close the file.

Finally, let’s see the result:

git log --oneline

This is what you should get:

As you can see, the three empty commits were replaced by a single commit. You’ve successfully performed your first squash. Congrats!

When You Shouldn’t Mess with History

Before wrapping up, let’s understand when changing history is problematic.

First, understand that both amend and rebase produce destructive changes. It’s like they’re destroying history and creating a new one.

So, imagine that you squash three commits (there were already pushed to the remote) into one and then push that new commit into the remote repository (you’d have to force push for that to work, by the way.) But while you were working, your coworker had branched off from (what was then) the latest commit.

That commit no longer exists (technically, that’s not quite true, but let’s pretend for a minute that it is), which means they won’t be able to simply push their changes. They’ll have to pull your new commits and then perform a potentially complex merge in order to get things sorted.

So, the golden rule is never rewrite history that other people depend upon. What this means in specific will depend on whatever branching workflow you and your team use.

If you use trunk-based development, never rewrite the master/main branch. The same is true if your work with GitHub Flow. If you use git-flow, that means never rewriting the “eternal” branches, i.e., master/main and develop.

OK, I Lied: Here’s a Bit of Theory

Throughout this post, I’ve been using language like “change the commit’s message”, “merge multiple commits into one”, and so forth.

Technically speaking, those were all lies. When you use commands like git commit --amend or git rebase -i, you’re not changing anything. What Git is doing is creating new commits.

Remember when you first used amend and I said that it was relevant that the commit now had a new identifier? As it turns out, that was an entire new commit, and the old one is still out there!

The same goes for rebasing. When you “merge three commits into one”, that’s not what’s happening. Instead, Git creates a new commit and updates the branch reference, so it points to the new commit. The three old commits are still there (at least for a while) but since no branch points to them they’re unreachable—unless you can get ahold of their SHA1 values somehow.

The following image represents what really happened after you squashed your commits:

Now, let’s see the scenario after the squash:

As you can see, there’s now a new commit, in orange, which is the result of “merging” the three original ones. However, the three old commits are still there. You can’t easily reach them, though, because now there’s no branch pointing to them.

The astute reader will notice that even the images above are a simplification. “We should have more commits in the image!”, they say, with their accusatory index finger pointing at the scream. And guess what, they’re right.

Remember we started this whole thing by amending two commits? Well, since amend doesn’t change commits but create new ones, we have two extra lost commits in our repository. I omitted them from the diagrams above because I was feeling kind of lazy for brevity’s sake. But as an exercise for the reader, you can add them yourself.

Rewrite the Past to Look (And Be) Smarter

Rewriting history is a powerful capability of Git. With commands such as git commit --amend and git rebase -i you can “change” your past commits, hiding your mistakes and making it look like you got everything right from the start. I do this all the time and I reap the benefits: my coworkers think I’m way smarter than what I’m really—please don’t tell them my secret.

Seriously now: these commands are fantastic tools for getting a more organized history. With them, you can lose the fear of committing frequently once and for all. Make commits small and frequent, and don’t pay too much attention to the message-for example, if you use TDD, you can commit every time the tests pass.

Then, when it is time to publish your work, squash the commits and put a nice description on them. Adopt a commit messaging convention for you and your team, such as Conventional Commits. Your colleagues (and your future self) will thank you.

Found a typo or mistake in the post? Suggest edit ← How To Reduce Cyclomatic Complexity: A Complete Guide The 5 Levels of Readable Code →